Morality 101

Are you a good person? If you say yes, how do you know you are? On what basis have you determined you are good?

I’m embarrassed to admit, I never gave a thought about morals until I was in my late 50’s. I grew up with a strong sense of right and wrong but I never took a class on morality, ethics, or even philosophy. Right and wrong was clearly defined and universally understood: stealing, lying and cheating was wrong, be kind & help others was good, etc. Yet, I look at our culture today and I see a slow-motion trainwreck, a complete breakdown in basic morals. From middle school thru college, the majority of kids these days think the only thing wrong with cheating or lying is getting caught. Even then, there is little shame. And sexual morality, well that is nearly non-existent now, with the “anything goes” slogan gleefully embraced. So just what is morality, where does it come from and why should we even care?

A Primer

Morality seems simple at first glance as “something everybody knows,” but it is actually a deeply layered and multi-faceted issue. As one starts digging below the surface it just gets more and more interesting and significant. Beyond a simple set of “rules,” we’ll see how morality is intrinsically tied to human rights, value, justice, meaning and purpose.

First, however, just what is the basic nature of morality? We can clearly see that morality is prescriptive, as it describes the way things “ought” or “ought not” to be, an unseen set of rules and obligations only known through an inner sense of “conscience.” And oddly enough, morality seems to be a fundamental aspect of reality just as much as gravity, sunlight or the laws of physics.

Click to enlarge

For example, here are two basic Truth Statements to consider:

Birds eat bugs and worms

It is wrong to mutilate and kill baby kittens for fun.

The first statement is an objective truth statement because it corresponds to physical reality, the way things actually are. It’s easy for us to observe that it is a true statement. But why do we consider the second statement true? How do we determine that it is really truth, a moral truth, and not simply a personal or cultural preference? Moral truths are not observable facts like watching birds eat bugs. Since we can’t see moral “wrongness” or “rightness”, can we call it a fact, a truth or a law? Most philosophers believe we can because there are other equally non-observable truths of reality such as the laws of physics, laws of logic and the laws of mathematics that rule and dictate our reality. So just because a moral truth is not observable doesn’t necessarily mean it is any less real or consequential.

Some basic principles about moral laws:

Moral truths include properties that can’t be observed but nonetheless have real consequences

Moral truths continue to be true even if no one ever mutilates kittens for fun - the laws of mathematics existed long before anyone ever discovered them and continue to exist whether anyone ever uses them.

Moral truths describe the way the world “ought” to be not the way it is.

Morals are rules that prescribe and govern behavior, our obigations and duties to act in certain ways.

Some moral “oughtness” rules are conditional (based on conditions) and some are imperative (non-conditional).

Moral laws were not invented or decided upon by humans. Like the laws of logic and mathematics, they are timeless and intrinsic to reality, discovered and not invented by humans.

Moral laws require a personal moral law giver. We do not owe obligations or duties to inanimate forces or objects, only to persons.

Preface

It’s important to note a couple of important distinctions right at the beginning. This article is mostly focused on the ontological basis of morality (why it exists) and not so much the epistemological (how we know it). Many people confuse these two when debating or considering morality. Anyone can know morality, but as we will see, worldviews such as atheism cannot explain why it exists. This is called the “grounding problem.”

In addition, we need to make the distinction between subjective morality and objective morality. This seems to be where the greatest confusion is for the majority of people. So first we need to define the difference between what is subjective versus objective.

“The atheist is cheating whenever he makes a moral judgment, acting as though it has an objective reference, when his philosophy in fact precludes it.” - William A. Dembski, mathematician & philosopher

Click to enlarge

Subjective vs Objective Morality

Subjective (internal)

When I say chocolate chip cookies with walnuts are the best cookies ever, that statement is a true statement. At least it is for me. It’s my personal taste opinion about cookies. Naturally, you may think I’m wrong, because to you snickerdoodle cookies may be the best. In either case, we are simply subjects having an opinion about something in the world. But our opinions about which homemade cookie is best tells us nothing about the nature or reality of the cookies themselves. Our subjective truth about cookies describes something about us, nothing about the cookies. Subjective truths always relate to and are based on the subject.

Unfortunately, in our current culture, too many people see all truth in the same way as their cookie preferences. A popular saying right now is, “That may be true for you, but not for me.” (Which is really just another variation on subjective truth called relative truth - see The Lost Truth about Truth article for more.) And that is a perfectly valid (true) statement when it comes to our favorite cookies, but too often these days it’s applied to everything else as well.

Objective (external)

Saying men cannot get pregnant is an objective truth statement. It’s called objective because it’s making a truth claim about a reality outside of our minds. Objective truths are externally based. They are not opinions that can be changed the way we change our shirt. They are features of the real world. When I claim that men cannot get pregnant, I am pointing out a fact of reality that men do not have the physical apparatus needed to develop an embryo and give live birth to a human baby. This is not a personal subjective opinion, but a statement about an objective, self-evident, demonstrable, physical fact. My opinion about it is irrelevant. So is yours. The way we determine if a statement is true is to look at the objects and see if the statement matches the reality.

Click to enlarge

Secular Laws & Morals

While all laws are based on morals (what is right and wrong to do), not all laws are moral. Slavery was once legal. Most people today will agree that didn’t make it morally right. In 1940’s Nazi Germany they passed a “Sterilization Law” mandating the forced sterilization of “undesirables” such as the mentally ill, Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals and the handicapped. An estimated 300,000 to 400,000 were forcibly sterilized against their will. The point here is that just because something is legal doesn’t automatically make it morally right.

Morality thus can’t be based on majority rule. People disagree, regimes change. Even today, some say abortion should be legal and is morally acceptable because a fetus is unborn and thus is not deserving of human rights. Others say the embreyo or fetus is still a human (it certainly won’t be a cat or a zebra) unborn or not and thus abortion is murder.

So who is right? Is what is morally right determined by majority vote or by whoever has the most power to enforce their will? Is there such a thing as objective right and wrong that is independent of humans? If so, how can we know what that is?

Beyond Religion

We tend to associate moral principles of right and wrong with religion, specifically with Christianity, and especially when it comes to sexual mores. And yet, basic moral principles existed long before Christianity or any recorded religion. Two thousand years before Christ, we can see the moral principle of honesty was present in ancient Babylonia, “With his mouth was he full of Yea, in his heart full of Nay?”

For example, The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed approximately around 1755–1750 BC. If you read the laws laid out therein, you see that theft, deceit, lying and treason were considered wrong, no different than our morals of today 3,750 years later - although their punishments were quite a bit harsher!

From the very beginnings of recorded history we know that chastity has been a virtue while adultery has been a shameful. In every culture throughout the world we find a strong sense of right and wrong, good and bad, of courage and integrity held up as righteous behavior, and deceit and treachery scorned as dishonorable. So we know religion has nothing to do with it…the strident atheist has been born with the same basic moral compass as the religious monk (if a bit more flexible!)

Click to enlarge

The Failure of Atheistic Moral Evolution

In order to mention the word evolution, we first need to define the term because there is a great deal of confusion around it. Darwinism, as it has been taught, is the slow and gradual change/evolution of species from simple to complex over millions of years. However, there are actually two basic levels of evolution in question: Micro Evolution, being the gradual changes seen when a species adapts to environmental pressures (finch beaks, cold viruses), and Macro Evolution, which states that those same micro changes somehow had us evolving from pond goo to fish to dinosaurs to humans, in other words from one kind of species to another.

Micro evolution is demonstrably true and observable, while macro evolution is not only not demonstrably true, it’s has scientifically and mathematically been proven to be impossible. Modern biologists are currently scrambling to find some other theory to account for the origin of entirely new species from apparently thin air. Random chance is simply impossible - but don’t take my words for it.

So what does this have to with morality? Well, according to atheists and materialists, we got morality from evolution. In other words, it evolved with us because it supports our survival. But if this were true, why haven’t morals “evolved” over the last 5000 years of recorded human history? If morals evolved to help us survive and thrive as atheists claim, why isn’t rape considered good? Wouldn’t rape enhance the survival of our species as it would spread more genes far and wide? If survival of the fittest and strongest is the source of morality, why isn’t slavery considered a moral and good thing - after all, the Roman civilization lasted over a thousand years based on slavery; that’s the best track record for a modern civilization to date. Hitler and the Nazi party believed wholeheartedly in survival of the fittest and thus their attempted extermination of the weak and “undesirables” to produce a master race. Why then does our moral conscience insist on the opposite - that we protect the weak, vulnerable and defenseless?

Darwinistic evolution says that we are products of unguided, undirected, random chance encounters of molecules over millions of years, making us nothing more than “moist robots.” But how does a random conglomeration of chemical reactions produce an immaterial moral law? Why would we have any moral obligation to obey chemicals?

Click to enlarge

Without an objective, external standard, independent of personal opinions, then all right and wrong is merely up for debate and there is no such thing as human value, rights or justice. If we are just accidental products of evolution then morality is an illusion and the rape and killing of a 8 yo child by a random stranger is of no more significance than a cougar killing a deer.

This evolutionary claim for morality is the declared belief of atheists and many non-Christians but it is not something they can live out. They can’t walk that talk. They claim there is morality but they have no way to ground or justify it. Their morality is entirely subjective and illusionary. If we really are just self-replicating meat machines created entirely by random evolutional accidents, then we have no more inherent value or rights than ants.

Justice, Purpose and Meaning

If morality is not objectively real, then the concepts of justice, purpose and meaning are, well… meaningless. They are simply self-invented delusions. But if morality is objectively real, then justice, human purpose and human meaning are something real and significant. What is curious, is that everyone lives as if morality is real, even those who simultaneously deny it.

Justice

Never is it more apparent that people believe right and wrong is real than when true evil rears its head. In April of 2009 an 8 yo girl was abducted as she walked home from school, driven an hour away into deep woods, raped repeatedly and then brutally beaten to death. It’s a horrific story and I only encourage you to read the story here in order that you might notice your reactions and see just how personally important the desire for justice burns in your heart.

Click to enlarge

True Justice has several components:

True justice must be impartial, applying to everyone equally

True justice must render to each what is due

True justice must be proportional

True justice must be based on an objective standard

Justice is a property of people, as there must be a mind and will involved.

Justice is the natural outcome of morality, the consequence of “wrong” actions. Yet without an objective standard of right and wrong, “justice” becomes random, arbitrary and meaningless. In order for us to pass true and fair judgement on someone, we must firmly believe in right and wrong as objectively real things, otherwise justice is a hollow concept. And everyone of us hungers for corrective justice and punishment for the perpetrators of an horrific rape and death of a poor 8 yo child.

Purpose

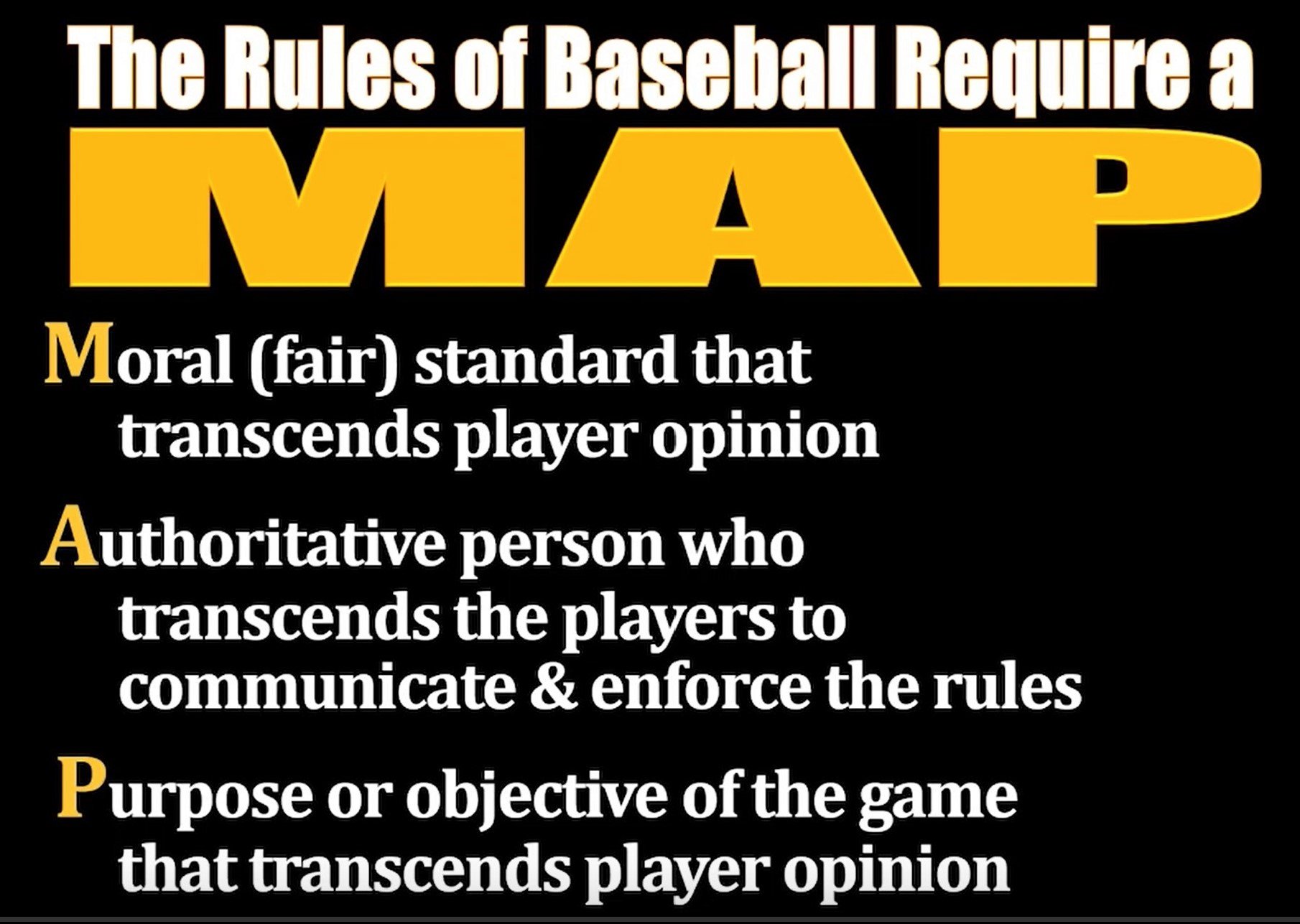

Throughout history, people have wondered if there was a purpose to their lives. The answer turns out to be surprisingly easy to ascertain. It is thru the “rules” of morality that we can see that our lives have a purpose. Imagine playing a game with a friend where there were no rules. You would quickly realize that without rules there would be no point to the game, no goal, no direction, no intention, just random movements. The rules of a game indicate its purpose. Yet purpose comes before morals because the purpose of a game dictates the rules that provide the order and restrictions . The author, Gregory E. Ganssle sums it up well:

The rules of a game correspond to the rules of morality

“The objective of the game of chess determines what the particular rules are. The rules might come first, though, in the order of knowing. I learn chess by learning the different pieces and the moves they are allowed to make. From there I move on to the goal of the game. The same relationship holds in the area of morality. In the order of knowing, the existence and nature of moral facts come first. These then give us a clue that there is a purpose… Someone invented chess and made up the rule about not moving your bishop across the horizontal. If the purpose that grounds moral obligations is one we cannot reject, it is probably not one that was invented by humans… So the nature of morality is a good reason to think that there is a purpose for human beings and that this purpose is not invented by people or society, nor is it optional”

Meaning

If there is no purpose to life, then life itself has no inherent meaning. How can there be any meaning to random accidents of mindless nature? Only if morality is objective can there be a meaningful purpose to our lives. A great little video about this can be seen here: Is There Meaning To Life by William Lane Craig on YouTube.

Purpose gives intent, morals provide the rules that direct us in the right direction and justice is the consequence of deviating from them.

The Standard of Morality

Imagine trying to build a house and every contractor from the framers to the plumber showed up with their own homemade tape measure… Obviously the house would end up a total mess, with nothing fitting properly and most likely non-functional. Somewhere back in the mists of time, someone realized that to build anything properly, everyone involved needed to be using the same standard unit of measurement.

In 1814, Charles Butler, a mathematics teacher at Cheam School (England), recorded the old legal definition of the inch to be "three grains of sound ripe barley being taken out the middle of the ear, well dried, and laid end to end in a row" Source: Wikipedia

When it comes to baking, in order to create a recipe for a cake it isn’t enough to simply say “add these ingredients in these amounts” (more standards needed here) but it also calls for baking the cake in an oven for a specific amount of time at a certain temperature. In the 1600’s, if a baker in England used a different measurement of temperature than a baker in India for the same recipe, the results were not favorable. Long story short, the boiling point of water became the point of reference that both bakers could understand and use.

Click to enlarge

Notice how in each instance, a standard was derived from an external objective source - in other words, something outside of humans that would be the same for every person on the planet was used as the standard. If the contractors and the bakers used their own personal, subjective standards, no cooperation would be possible.

Humanity has historical records dating back 5000 years. Throughout all of recorded human history we can see this idea of right and wrong behavior has been in integral part of the human psyche. To all appearances it seems to be endemic…try to imagine a reality where there is no such thing as right or wrong, good or bad. It’s clearly embedded in the “system” of our universe.

That there is such a thing as moral right and wrong is without question. The only question that arises then is whose idea of right and wrong is…well, right or wrong. The problem with that question is that it assumes that morality is subjective or relative, that one person’s idea of what is right and wrong can be different from someone else’s.

At first glance there sometimes appears to be conflicts or differences between cultures. Americans love their steaks and cows are for eating. Yet cows are sacred to Hindu’s, as they believe they may be reincarnated ancestors. That appears to be a moral conflict. Upon closer examination, however, we see that there is no conflict: both cultures see eating or dishonoring your elders or ancestors as wrong. The only difference is Americans don’t have the culture belief that the steak they just ate might be Uncle Ted.

When we look back on all of recorded human history we see the same pattern of basic morality. In no culture has cowardice been venerated more than courage, killing innocents seen as virtue, betrayal valued more than loyalty, or stealing from your friends seen as righteous. Instead, throughout all time we see loyalty, integrity, love, kindness, courage, generosity and honor held up as virtuous and good.

“If we can find even one moral rule that would apply objectively to all people, times and places, then objective moral laws exist.” Jimmy Wallace

Click to enlarge

So what is the Standard of morality? How do we know something is good or something is bad? In order to determine that something is bad, we need an external point of reference to judge it by. Without an objective standard of right and wrong, all moral laws would be subjective, a matter of preference, and there would be no way to say that mutilating kittens for fun is wrong because that would be invoking an objective standard.

I once saw this popular quote on Facebook, “Wrong is wrong, even if everyone is doing it. Right is right, even if no one is doing it.” No one disagreed with the post, including me. But it begs the question: WHO determines what is right and wrong? One commenter wrote, “Right and wrong are subjective, usually ingrained in us by opinions of those we trust to teach us and who we look up to. What is wrong for me may be right for you.” Now that is a perfect example of subjective relativism and even a few moments of careful thought should see the flaw in that logic. If stealing is right for the thief, then how can he be wrong for stealing? If right and wrong are subjective as that commenter wrote, then it’s all just a matter of personal preference; the thief prefers to have your money and you prefer he doesn’t. And your preference is no more valid than his preference.

By that logic, Hitler was not “wrong” for murdering millions of people. So who’s opinion gets to decide who is right and wrong? If Nazi Germany had won World War II, would the killing of millions of Jews, homosexuals and other “undesirables” in the gas chambers have thus been “right?” Does that mean that “might makes right?”

Of course not. So somehow our sense of right and wrong, good and bad, has to be objective, independent of human opinion, thoughts or beliefs. Atheists and materialist want to claim morality is wired in by evolution, a survival mechanism for the species. But that presupposes that survival of the species is a good thing, which is itself a moral value judgement. Where do we get the idea that survival of the species is a good thing?

An Atheists Moral Argument Against God

The actor and comedian, Stephen Fry is an angry atheist. Like his fellow comedian, Ricky Gervais, he literally hates God and he is quite vocal about it: “It’s utterly, utterly evil. Why should I respect a capricious, mean-minded, stupid God who creates a world which is so full of injustice and pain?” His feelings and opinions are shared by millions of people around the world. The first time I was told about Christianity by a friend in High School, I had nearly the same reaction. My thought at the time was, “I’m more compassionate and loving than God, so I certainly can’t believe in a god like that.”

What I (and all these angry atheists) never considered was the very basis of morality. Where does it come from? What makes you or I the arbitrator of what is right or wrong? And atheists never confront their own ideological illogic of insisting on one hand that we are nothing but undesigned, accidental mutations of random chemical reactions, while on the other hand insisting that immaterial feelings produced by those undesigned, accidental, random molecules in their brains is somehow real and relevant.

You can’t have it both ways. Either morality is real, which means it has to be objective and transcendent or atheism is real, morality is just meaningless opinion because there is no transcendent God, which begs the question, why is the atheist so angry? This is how I know atheists actually believe in God - if they truly believed what they espouse, they wouldn’t be angry. You can’t hate what isn’t real.

Click to enlarge

Final Thoughts

So now we finally get to the Big Question, the important question, the elephant in the room no one wants to address question: What is the Standard of Good by which we judge all behavior? If Hitler who systematically murdered over 6 million people in the gas chambers is considered BAD, and Mother Teresa who devoted her life to caring for the poor and destitute in Calcutta is considered GOOD, what yardstick are we using to determine their goodness/badness? And to follow that out logically, what is the ultimate good at one end of the yardstick, and the ultimate bad at the other end?

When all tend to debauchery, none appears to do so. He who stops draws attention to the excess of others, like a fixed point. The licentious tell men of orderly lives that they stray from nature’s path, while they themselves follow it; as people in a ship think those move who are on the shore. On all sides, the language is similar. We must have a fixed point in order to judge. The harbour decides for those who are in a ship; but where shall we find a harbour in morality? - Blaise Pascal

Unless there is some objective standard of good beyond Hitler and Mother Teresa then there is no such thing as right or wrong, it’s just his opinion against hers and neither can claim being right. Ultimately, without God as the ultimate standard of Good, there is no basis for objective good or bad, right or wrong. Disagree? Then what is an alternative, external, objective reference for moral good? It can’t be an impersonal force or thing such as gravity or evolution… it has to be a person, because only persons with a mind and free will can be moral. And moral laws can only come from a moral law giver.

Some additional reading on Morality:

What Criminal Trials Teach Us About Objective Moral Truth by J. Warner Wallace

Can Atheism Account For Morality? by Ryan Leasure

Confusing Moral Utility With Moral Creation by J. Warner Wallace

Objections to Objective Morality by Cole James

On The Moral Argument

How To Force Your Morality by Greg Koukl

The Case for a Personal God from Morality: Justice by Stephen S. Jordan

Three Questions that Show the Insanity of Modern Moral Outrage by Adam Tucker

Throwing off the Shackles of Morality by James

What Must Be True for Ultimate Justice to Exist? by Amy Hall

Moral Argument (part 1) by William Lane Craig

Moral Argument (part 2) by William Lane Craig

Moral Argument (part 3) by William Lane Craig

Moral Argument (part 4) by William Lane Craig